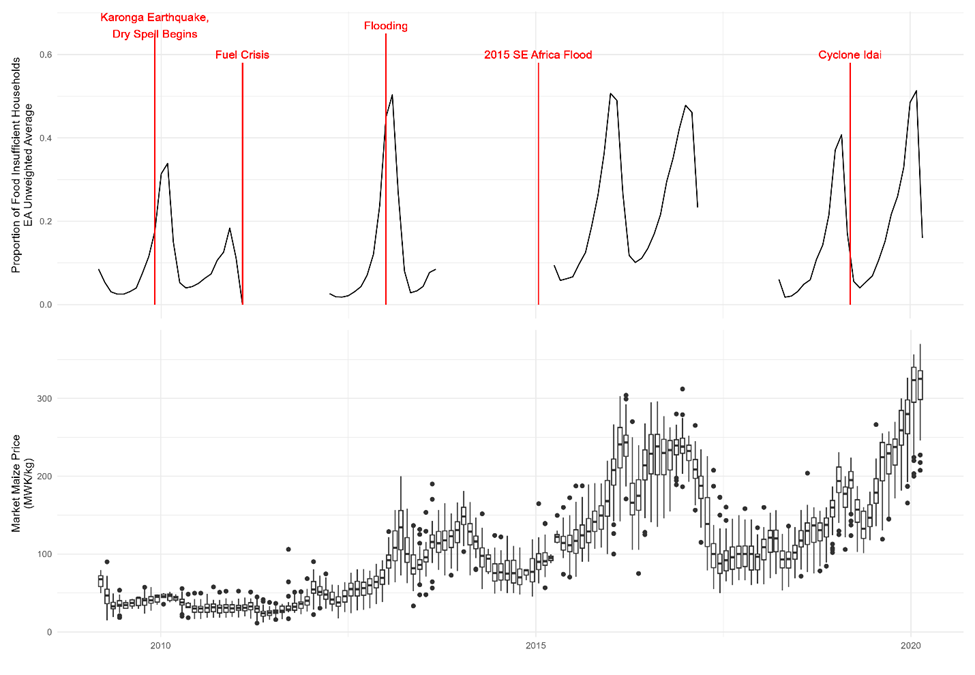

In 2023, approximately 282 million people across 59 countries faced severe food insecurity, an increase of 24 million from the previous year. Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) bears a disproportionate burden of this crisis. Climate change is already reducing cereal production across the region, with projections showing a further 20% decline by 2030. Food import bills in Southern Africa surged from $35 billion to $43 billion between 2019 and 2022. Africa is off track to meet the Sustainable Development Goal of ending hunger by 2030 and the Malabo Commitment to reduce poverty by half by 2025. Climate variability, rising temperatures, shifting rainfall patterns, and increasing frequency of droughts and floods, is fundamentally reshaping agricultural systems. Responding to climate shocks requires evidence-based policy, yet a significant gap persists between the availability of climate data and its practical usability for agricultural policy analysis.

The Data Access Challenge

High-quality climate datasets are increasingly available. The Climate Hazards Center (CHC) provides CHIRPS precipitation and CHIRTS temperature data at high resolution. NASA and other agencies offer temperature and vegetation data. These datasets are often free and well-documented, but “available” does not mean “accessible.”

Desktop software like GeoCLIM requires users to install QGIS, download several gigabytes of raw data, and have GIS expertise. Web-based alternatives like the Early Warning Explorer eliminate software installation but typically limit users to rectangular map regions and single-year time periods. Tableau needs pre-constructed datasets requiring massive storage. Most web tools provide only basic statistics rather than derived indicators that help identify drought-prone areas or understand seasonal dry spells. When researchers cannot easily access climate data, policy-relevant analyses either may not happen or rely on national-level averages that obscure local variation critical for small-scale producer (SSP) agriculture. The Ag GeoSpatial Data Explorer (AgGeo) addresses these barriers through a web interface that processes data on-demand, follows actual administrative boundaries, and allows custom seasonal definitions matching agricultural calendars.

How the Climate Data Explorer Works

EPAR’s Center on Risk and Inclusion in Food Systems (CRIFS) developed AgGeo to address these challenges. Rather than requiring users to download and process data locally, the platform processes climate data on-demand and delivers results through a web interface. This directly tackles the software installation, bandwidth, and technical expertise barriers.

The platform covers countries across sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. It is built on public datasets: The CHC’s CHIRPS provides precipitation data over four decades, while GAEZ provides spatial classifications of land use.

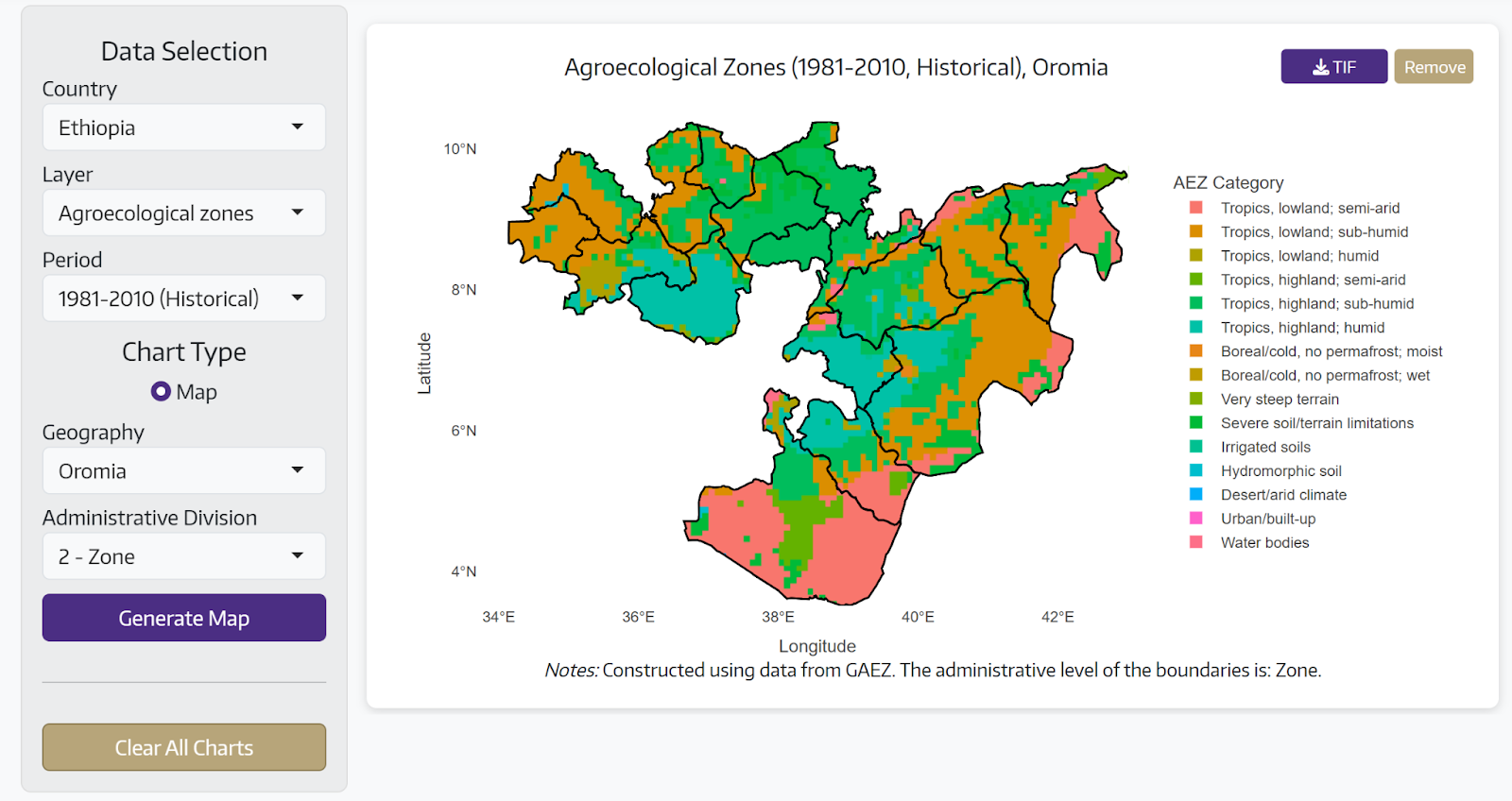

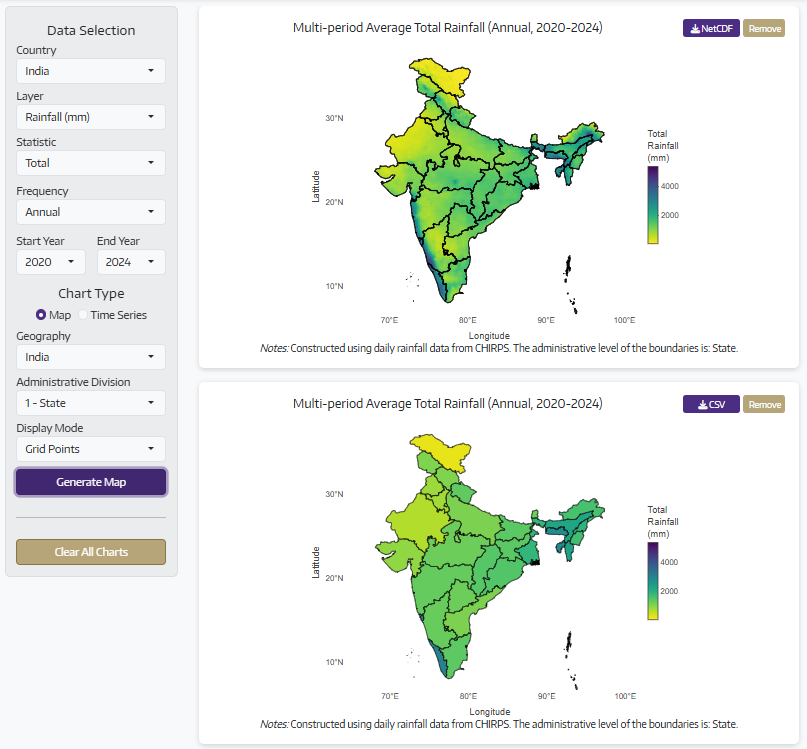

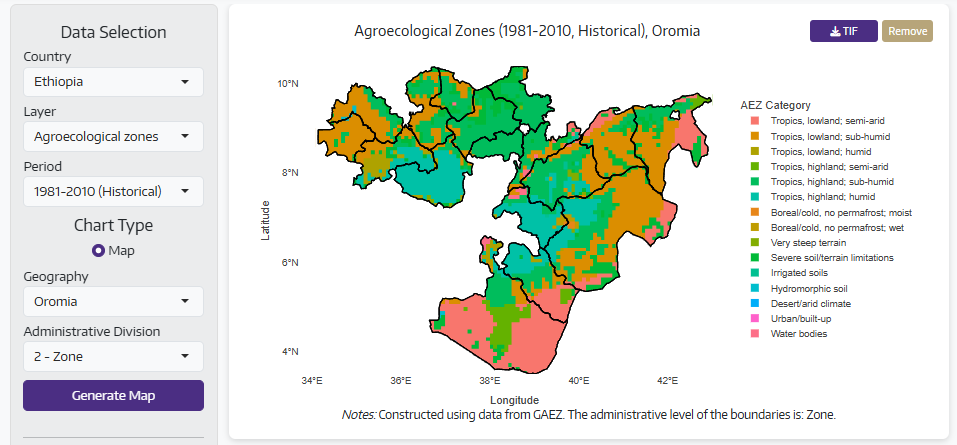

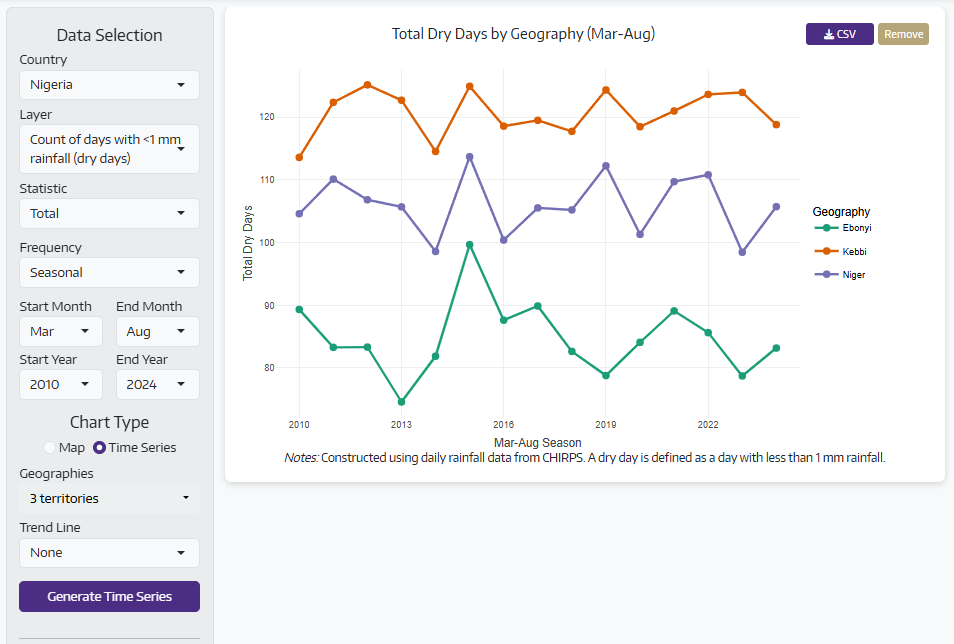

Users select their country, layer, and time period through a sidebar interface. The tool offers annual trends, seasonal patterns, monthly details, or quarterly summaries. Users choose between interactive maps (detailed grid values or regional averages with color-coded boundaries) or time series charts that are rendered within seconds. Users can hover over locations for exact values, zoom into regions, compare multiple territories, and download visualizations.

What the Tool Provides

AgGeo currently offers three layers that help researchers and policymakers understand climate variability and its agricultural implications.

Rainfall volumes track precipitation. Users can calculate total rainfall for any time period, understand typical rainfall intensity through daily averages, and compare across different regions. This helps identify wet and dry seasons, understand year-to-year variations, and spot long-term trends. Researchers can analyze data annually, seasonally, monthly, or quarterly, depending on their specific questions.

Dry days monitor drought patterns by counting days with minimal rainfall. This indicator helps identify drought-prone areas, understand when and where seasonal dry spells occur, and assess water availability during critical growing periods. Knowing how many consecutive dry days occurred during planting or flowering stages reveals much more about potential crop stress than total seasonal rainfall alone. This information helps target drought-resistant varieties or irrigation investments to the areas that need them most.

Agro-ecological zones visualize agricultural potential based on climate, soil, and terrain. The tool shows both current conditions and future projections, helping researchers and policymakers understand which areas are suitable for different crops today and how climate change might shift these zones over time. This supports long-term agricultural planning and adaptation strategies.

Users can explore climate patterns at multiple administrative levels, from entire countries down to individual states, districts, or smaller regions. The ability to compare multiple territories side-by-side helps understand regional differences and identify areas facing similar climate challenges.

Why This Matters for Policy

Accessible climate data enables critical policy-relevant analysis. National planning offices can map rainfall variability to identify regions requiring different crop strategies or irrigation investments. Understanding spatial patterns helps target interventions effectively.

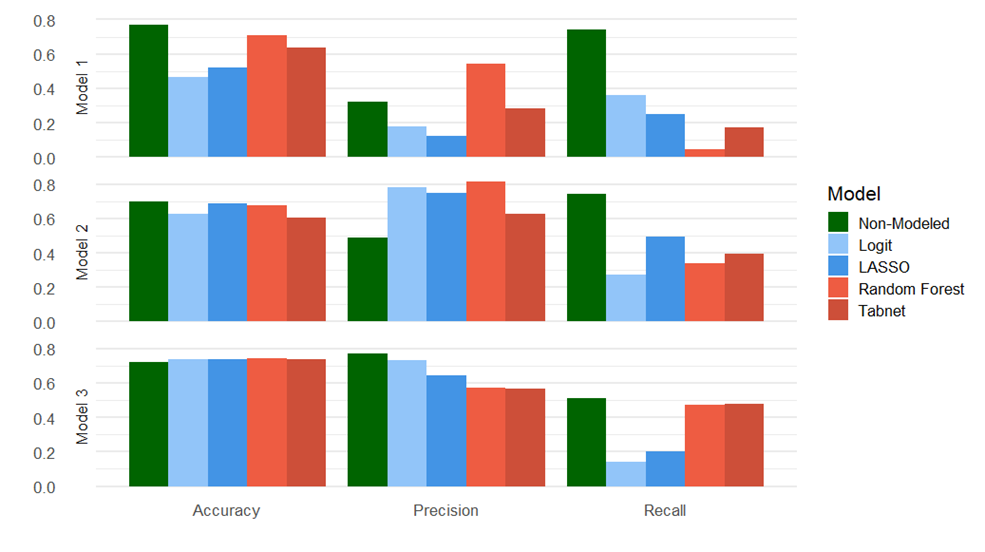

Program evaluations benefit from climate control variables that distinguish program effects from environmental factors. Food security monitoring reliability increases when analysts can quickly compare current rainfall to historical patterns, identifying regions at risk of production shortfalls. Researchers can identify drought-prone areas and analyze long-term trends to support climate adaptation planning.

Upcoming Features

The platform currently provides comprehensive coverage across sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. Users can generate interactive maps and time series charts, compare multiple territories, and download results in multiple formats.

In the near future, EPAR plans substantial expansion including standardized drought indices, temperature anomalies, growing degree days for crop development tracking, and vegetation health monitoring. Integration plans include adding AgGeo within AgQuery+ and overlaying LSMS-ISA enumeration area coordinates for direct linkage with household survey data.

Getting Started

The Ag GeoSpatial Data Explorer is available at https://agquery.org/aggeo. The interface is designed for users without technical training. Select your parameters, generate visualizations, and download data through your web browser. You can click on the ‘About’ tab in the top-right corner of the app to learn more.

To cite this tool: UW EPAR (2025). Ag GeoSpatial Data Explorer: A platform for constructing and visualizing geospatial indicators for sub-Saharan African and South Asian countries.

EPAR welcomes feedback and suggestions for platform improvements. More information about EPAR’s work on climate and food systems is available at epar.evans.uw.edu.

Blog written by Apurwa Rahulkar and Joaquin Mayorga.