Research and development (R&D) is work that pertains to innovation, introduction, and improvement of products and processes. The R&D process for new products and services often takes years and large investments to come to fruition, and funders face the risk that some investments may fail to generate returns to investors or benefits to users. Thus, estimates of the costs, risk, and potential returns to R&D projects all influence funders’ decisions around where to invest.

The knowledge resulting from R&D is what economists call a “public good,” because many people can simultaneously benefit from an innovation like a new vaccine, medical treatment, improved seed variety, or agricultural technology without diminishing its value to others. Because of potential widespread benefits, agricultural and health R&D tends to attract a large amount of public and philanthropic funding. But in addition to “non-rival consumption” public goods also have the characteristic of being difficult to charge for, an “inability to exclude non-payers.” For the private sector, difficulties in charging for use of knowledge once created may limit the potential to profit from some R&D investments. Patents and other intellectual property protections create some excludability where they are enforced, incentivizing private sector investment.

From a global planning perspective, an efficient allocation of scarce global R&D funding would involve matching private, public, and philanthropic resources to various different R&D types, taking into consideration each funder’s underlying motivations and goals. In the broadest terms, private investors can be assumed to seek to maximize profit, public funders are motivated by a broader set of political, economic, and social goals, and philanthropic funders aim to maximize some form of social rate of return on their investments. Social returns might include, for example, increased food security arising from an investment in food crop R&D, or increased resistance to particular diseases arising from investments in new vaccines.

To maximize and efficiently allocate global R&D funding, any economically profitable endeavor would first be undertaken by the private sector, and the public and philanthropic sectors would fill in the remaining gap up to the socially optimal level. The reason for this “two-stage” process is that the opportunity cost of a dollar of private funding is arguably lower, since we assume that non-private investors may seek financial or social returns, but private investors will limit their range of investments to those with positive financial returns. Hence efficiency requires that the private sector – given current market and regulatory conditions – first fund the subset of investments that meet their more limited objectives. A recent EPAR review of available data on global funding for agricultural and health R&D by sector finds some evidence suggesting patterns in global R&D investments may align with theoretical expectations for efficient global funding allocation.

Agricultural R&D: Where Are The Resources Going?

Agricultural R&D includes investments in agricultural technologies that can improve farmers’ yields, increase production and profitability, and connect farmers to markets. R&D in agriculture can also provide various benefits to society, such as promoting regional food security and sustainable use of natural resources. A 2000 IFPRI meta-analysis found that globally, on average, $100 of agricultural R&D invested yielded $199.60 in social benefits, beyond the private financial return.

Data on agricultural R&D spending outside the public sector are limited, but IFPRI’s Agricultural Science and Technology Indicators (ASTI) database indicates that in 2008, the public sector provided 79% of funding for agricultural R&D, compared to 21% for the private sector. Economic theory suggests private R&D funding will focus on cash crops and commonly-traded, market-oriented commodity crops, as farmers might be more willing and able to pay for these new technologies, leading to greater potential for private sector profit. Fuglie (2016) estimates that in 2014, private companies (mostly in high-income countries) spent $12.9 billion on agricultural R&D. The same report finds that private investments focuses on large-acre market-oriented crops, in particular corn, soybeans, and wheat, in addition to small-acre cash crops like fruit and vegetables, consistent with expectations that private funders might focus on R&D investments likely to accrue higher short-term financial returns and profits. Several other studies also find that private R&D mostly targets cash crops and hybrid varieties, with limited funding targeting subsistence crops.

Public institutions play a primary role in funding basic agricultural R&D, investing $31.7 billion in 2008. A recent EPAR visualization shows the distribution of public agricultural R&D investment in Sub-Saharan Africa in 2011 using data from the ASTI. Because public R&D is motivated by social objectives such as national food security as well as financial objectives such as economic growth and development, we would expect public sector investments to target both cash crops and subsistence crops. R&D for subsistence crops offers lower potential financial returns but significant potential social returns from nutrition and food security gains.

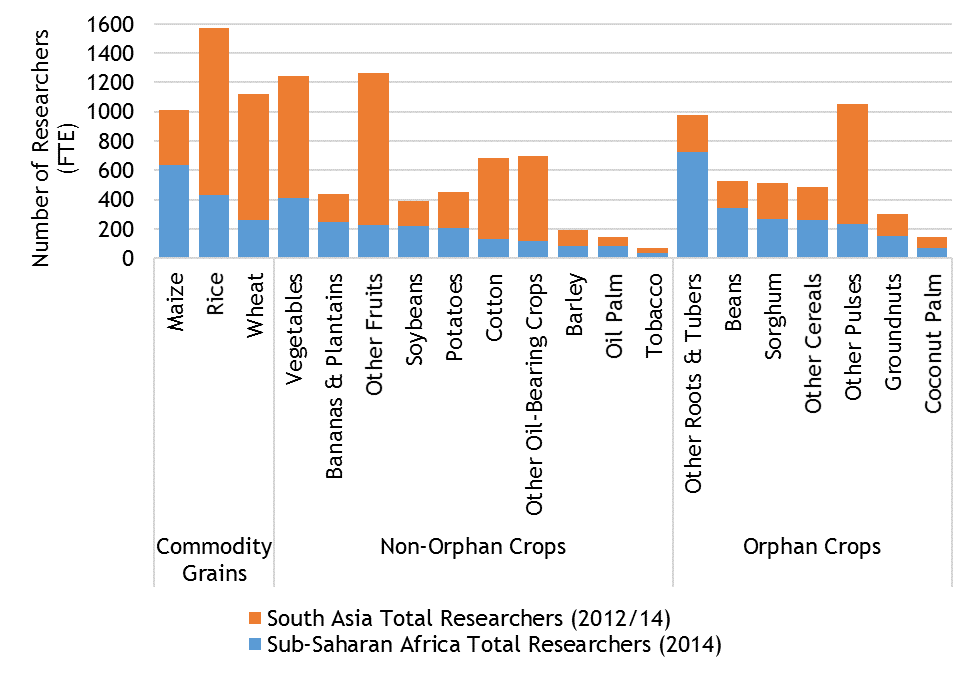

The figure below illustrates the number of public researchers focused on different crops in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and South Asia (SA) using 2014 data from the ASTI. Similar to private R&D spending, public investment as indicated by the number of Full-Time Equivalent (FTE) researchers focuses primarily on market-oriented commodity grains and cash crops like fruit and vegetables. Several “orphan” crops grown primarily for subsistence also receive public R&D funding, however, suggesting that considerations of social returns from investing in these crops may influence public R&D funding decisions in these regions.

Data on philanthropic investments in agricultural R&D are limited. A FAO report estimates that 25% of agricultural development funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) goes to R&D, for a total of $45 million in funding for R&D in SSA in 2009, placing it in the top five for bilateral and multilateral donors to R&D in SSA. According to OECD’s Creditor Reporting System, the BMGF disbursed approximately $153 million for agricultural research in developing countries in 2015.

Data on philanthropic agricultural R&D investments by crop are also limited. According to the 2011 Gates Foundation agricultural development strategy overview, three of the five largest BMGF grants for agricultural R&D from 2003 to 2010 targeted maize and wheat, more market-oriented crops, but another grant specifically targets staple crops and the largest of the five grants supports local public and private capacity building for agricultural R&D in SSA. If this pattern holds for other philanthropic investments in agricultural R&D, it would suggest that, like the public sector, the philanthropic sector funds R&D for both market-oriented and subsistence crops. According to some studies, there are a growing number of partnerships between private, public, and philanthropic organizations, which may lead to overlapping investments.

Health R&D: More Specialization for “Neglected Diseases”

As with agricultural R&D spending, investments differ across sectors for health R&D. New health technologies can improve health and educational outcomes, boost incomes, and contribute to herd immunity and other social benefits. According to a review of global trends in biomedical R&D expenditures, the private sector provides a majority of overall health R&D funding worldwide, with companies in the United States, Europe, Canada, and Asia-Pacific Region investing $168.7 billion in health R&D in 2012. Most private investment targets non-communicable chronic diseases, such as different forms of cancer. These diseases, though increasingly prevalent in low-income countries, also affect high-income countries whose populations have a greater ability to pay.

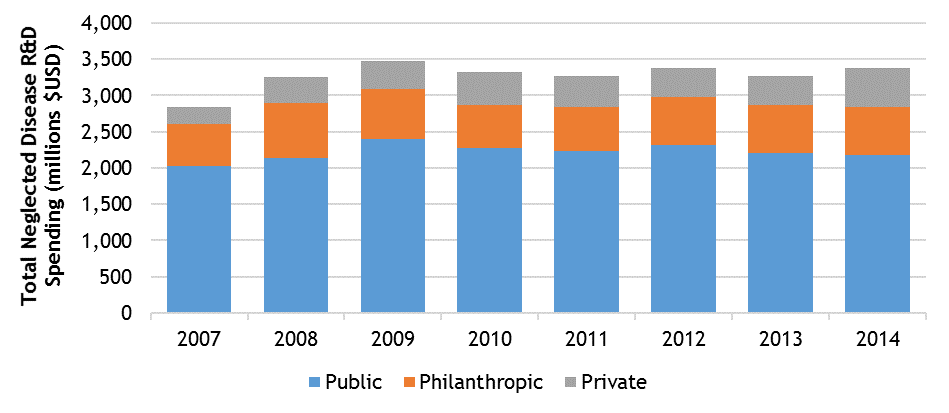

Though the private sector provides the majority of funding for global health R&D overall (62.9% in 2012), they provide just 16% of funding for “neglected diseases,” including HIV/AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis, and 17 other diseases that disproportionately affect people in developing countries, according to Policy Cures. The remainder of funding for these diseases comes from the public sector (64%) and the philanthropic sector (20%). This suggests that private funders may focus on health R&D for diseases prevalent in higher income areas, as opposed to diseases that are more concentrated among poor populations.

In 2012, the public sector in the United States, Europe, Canada, and Asia-Pacific Regions spent $99.6 billion—accounting for 37.1% of all health R&D funding. While the public sector provided $2.165 billion of funding for neglected diseases in 2014 – 64% of the total for these diseases – this represents just 2.2% of total public sector health R&D investment. The majority of public neglected disease R&D funding targets the “Big Three” neglected diseases – HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis, which together account for 5.6 million deaths and the loss of 166 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) annually.

A separate review of health R&D data reports that the philanthropic sector accounts for 10% of global health R&D investment. A report on the ten largest public and philanthropic funders for overall health R&D in 2013 found that the top philanthropic donors were the Wellcome Trust ($909.1 million), Howard Hughes Medical Institute ($752.0 million), Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation ($462.6 million), and Institut Pasteur ($220.9 million). According to Policy Cures, philanthropic sources provided $678 million to R&D targeting neglected diseases in 2014, accounting for 3.2% of total philanthropic health R&D spending. Similar to the public sector, the “Big Three” diseases are the top philanthropically-funded diseases, accounting for 67% of philanthropic neglected diseases R&D funding.

Funders from the public, philanthropic, and private sectors allocate a very small percentage of their health R&D investments to neglected diseases. However, the distribution of funding for neglected diseases does suggest some degree of specialization, as the public and philanthropic sectors take on a larger role than for overall health R&D spending. The figure below illustrates R&D spending on neglected diseases by sector between 2007 and 2014 using data from the Policy Cures G-Finder reports, illustrating the minimal role of private sector.

What does this mean in terms of ensuring funding for R&D with public good characteristics?

Although in both agriculture and health the majority of R&D funding from all sectors targets crops and diseases with greater potential financial returns, we do find that the public and philanthropic sectors play a bigger role in funding R&D with lower financial returns but high social returns, such as subsistence crops and neglected diseases. We also find that the public and philanthropic sectors invest more in early stages of R&D, where potential returns are most uncertain. Some data suggest that this trend is also apparent in agricultural R&D.

There is little consensus on the “best” way to ensure the provision of R&D with public good characteristics. This is especially relevant in low-income countries such as those in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, where subsistence farming and neglected diseases are common and private funding levels are low. More data are available on health R&D investments than on agricultural R&D investments. Data for agricultural R&D by the private and philanthropic sector are particularly limited, although the global landscape of agricultural R&D is changing fast. Efforts to collect, analyze, and disseminate data on private, public, and philanthropic R&D investments could lead to more efficient allocation of scarce R&D funding and create opportunities for partnerships between sectors.

By Karen Chen

Summarizing original EPAR research by C. Leigh Anderson, Travis Reynolds, Pierre Biscaye, & Matthew Fowle