At first glance, one might presume the answer to this question to be an emphatic “always”. After all, these systems are designed to shield communities from severe environmental hazards, thereby boosting agricultural productivity, so it would seem that farmers would jump at the chance to use them. In reality, however, even when access isn’t a barrier, the use of Early Warning Systems can vary (Sharafi et al., 2021; Andersson et al., 2020). This raises some interesting questions: What drives some farmers to embrace EWSs? What holds others back? And how can research on climate risk communication help improve the adoption of these life-saving technologies?

In exploring these questions with existing literature, EPAR PhD student Nnenna Ogbonnaya-Orji conducted a Web of Science (WOS) search using the criteria “early warning system” AND farmer AND climate on studies published between January 2015 and March 2025. The majority of studies retrieved were focused on early warning systems pertaining to specific hazards, most notably droughts. Papers were excluded for one or more of the following reasons: either they did not address factors relevant to the uptake of early warning systems or other weather/climate information service; focused on advanced economies, or did not pertain to the early warning of climate-related events or disasters.

Why EWSs Matter to Farmers in Low- and Middle-Income Countries

Climate adaptation is increasingly critical for agriculture, especially rainfed and small-scale producer systems in countries where farming is not just an economic activity but a way of life, woven into social and cultural fabrics. In these regions, farming is often tied to deeply rooted beliefs and traditions. This creates a complex decision-making environment that makes it difficult to promote new information-based technologies. The high uncertainty of climate impacts introduces cognitive biases, which further complicates decisions to adopt new practices and technologies.

Though definitions of EWSs may vary, they all revolve around two main goals: detecting risks early and advising specific actions to reduce impact. Risk in this context is defined as the probability of an adverse event occurring, with its impact contingent on the frequency and intensity of exposure to the event and the capacity to mitigate or adapt to it (IPCC, 2022). Exposure and vulnerability depend on the scope and scale of the particular event, and are shaped by socioeconomic and political factors such as literacy levels, access to infrastructure, government policies and priorities, and trust in institutions – which in turn, influence how warning messages are communicated and the extent to which they prompt action. Therefore, to be effective, EWSs must be regularly updated and customized to fit the changing dynamics of local contexts. A key component of many EWSs are Seasonal Climate Forecasts (SCFs), which estimate rainfall and other important meteorological variables for periods ranging from months to entire seasons Despite increased availability, and proven gains to agricultural yield (e.g. see Lupiya et al., 2024), adoption among farmers is, at times, considered suboptimal (Andersson et al., 2020).

What drives EWS Adoption by Farmers?

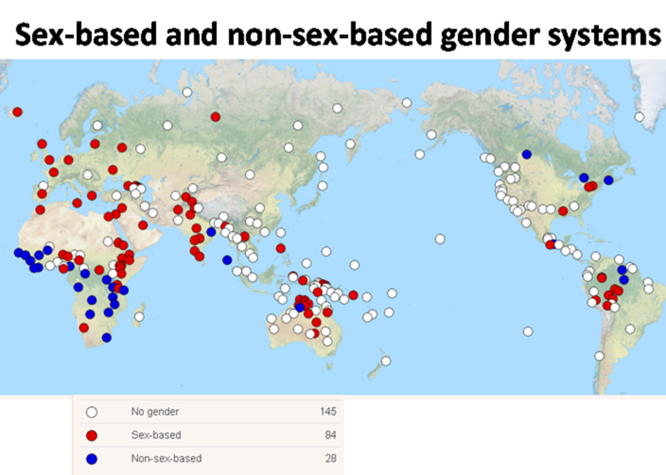

Though some progress has been made in recent times, not all countries have functional EWSs. As at 2023, 69 of 100 countries assessed under the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction reported having “comprehensive coverage” of local or national dissemination mechanisms for early warning information (WMO, 2023). Notably, none of the 11 Least Developed Countries (LDCs) assessed were included in this number – highlighting wide disparities in EWS access and significant knowledge gaps on the nature of this problem, especially as it pertains to developing countries. In some contexts where this technology is available, some evidence suggests that uptake by farmers is low, due in part, to a range of socio-cultural, demographic, economic, and institutional factors. For example, wealth and socioeconomic status reportedly play a big role in determining which farmers have access to these technologies, meaning that uptake can be limited to those with more resources (Nyoni et al., 2024). Adoption by farmers has also been found to be more likely with higher literacy rates and less likely with increasing age (Kolawole et al., 2018). Relative to other climate smart agricultural practices, information-based interventions such as EWSs are distinct in their primary reliance on effective communication rather than on physical tools or techniques. In Sub Saharan Africa, for example, low uptake of weather and climate services has been linked to limited comprehensibility of forecast information, inappropriate use of language and perceived incompatibility with indigenous practices (Nkiaka et al., 2019). Thus, to dig deeper into what drives EWS adoption, it helps to break down the communication process. Berlo’s (1960) SMCR model (where SMCR denotes the Source, Message, Channel, and Receiver), offers a useful framework for exploring these factors.

The Source of the Message Matters

EWSs are often managed and delivered through a top-down structure, starting from national or regional levels and moving down to local authorities, who then communicate with end-users (Andersson et al., 2020). This structure means that how farmers view the credibility of the government or scientific institutions often influences their trust in these systems. In many low-income countries, farmers rely on traditional sources of weather information, embedded in their cultural frameworks, rather than on scientific sources. For example, a study in North Central Namibia found that while about 50% of households accessed climate information, many still found it insufficient and continued to trust traditional knowledge instead (Gitonga et al., 2020). Promising paths to circumventing this challenge emphasize scientific interdisciplinarity and participatory approaches to the design and delivery of EWSs (Van Ginkel & Biradar, 2021; Walker, 2021; Hermans et al., 2022).

Trust in the Message Itself

It’s not just about who delivers the message, but also about the message’s content, quality, and clarity. Farmers need to feel confident that the information is reliable and relevant. For an EWS to build this confidence, it typically needs to deliver consistently accurate and precise forecasts—a tall order given the high uncertainties inherent in climate modeling. This is complicated as communicating these uncertainties without compromising message credibility is difficult. Furthermore, many low-income countries lack the resources needed for up-to-date methods, further limiting the system’s ability to generate reliable predictions.

Studies also show that how a message is framed can impact its reception in a given context. For instance, Calvel et al. (2020) found that small-scale farmers in the Mangochi and Salima Districts of Malawi adopted and responded to early warning messages when framed as advice pertaining to agricultural practices (what to do) as opposed to weather-related information (when to do it). In a study of coastal communities in Vietnam, Ngo et al. (2022) found that when messages were more concrete, and framed as gains, they led to a stronger risk awareness and intent to act on climate adaptation than abstract- or loss- framed messages. To be effective, they conclude, EWS messages should be clear, culturally relevant, and specific in the actions they ask farmers to take.

Reaching Farmers: The Importance of Communication Channels

Whether it’s traditional media, new digital platforms, or word-of-mouth, the medium of communication is critical to broadening EWS access and uptake. Thus, to be effective, EWS messages must be disseminated via communication channels that are tailored, contextually relevant and accessible. This can be challenging, as in many poor or remote regions, access to these channels remains limited and can vary along gender lines, making it difficult to reach all potential users.

An illustrative case is the flood devastation of rural communities in Delta state, Nigeria despite timely early warnings disseminated via mass media. In a qualitative study, Ebhuoma & Leonard (2021) found that fatigue after a long day of work prevented farmers who owned radios from tuning into local news, while poverty restricted access to television broadcasts, suggesting that more personalized communication e.g. via extension workers may have been more impactful. Using intrahousehold survey data, Ngigi & Muange (2022) report gender variations in access to climate information services and preferences for specific communication channels. Whereas husbands were found to have significantly more access to early warning systems and advisory services on adaptation than their wives, wives were shown to have greater access to weather forecasts than their husbands. Additionally, husbands indicated a greater preference for obtaining climate information services from extension workers, print media, television and local leaders, while wives preferred to obtain such information from their social networks and/or the radio. Other channel-relevant challenges cited in literature include delays in data exchange between agencies and the need for timely, multi-channel dissemination, all of which can affect the salience of EWSs in local communities.

Understanding the Receiver

For EWSs to be impactful, they need to engage with farmers’ perspectives on risk and adaptation. Some factors, like innate cognitive biases, may be harder –if not infeasible – to address. But others, such as perceptions of self-efficacy and adaptive capacity, can be influenced through well-crafted messages. Research shows that with a higher material cost of adaptation (e.g. buying drought-resistant seeds or hiring equipment), discrepancies between plans and actions tend to widen (Sutcliffe et al., 2024). This suggests that when economic constraints prevent adaptation, communication strategies can sometimes help bridge the gap by fostering a sense of control. Farmers may be more likely to act if they feel capable of managing risks despite limited resources.

Bringing It All Together

The SMCR model focusing on the Source, Message, Channel, and Receiver provides a useful framework for dissecting the complex and layered communication environment in which farmers operate. By addressing gaps in trust, message framing, communication channels, and farmers’ perceptions, researchers and policymakers can improve EWS adoption, ultimately helping farmers make more informed, adaptive decisions in a changing climate.

There is no simple answer to why some farmers use and respond to climate information while others do not. Risk perception, often influenced by cognitive biases, remains a central factor in these decisions, but Early Warning Systems (EWSs) can also be optimized to improve uptake. EWS deployment must balance environmental and economic benefits with social realities to be effective in different cultural and economic contexts (Sharafi et al., 2021). Practical barriers, such as limited forecast precision, comprehension challenges, weak infrastructure, and perceived self-efficacy, underscore the need for EWS designs that engage local communities in identifying social priorities (Andersson et al, 2020; Otieno et al., 2024).

Studies suggest the importance of integrating EWSs with indigenous knowledge systems to build trust and foster effective two-way engagement with end-users of warning messages (Fragaszy et al., 2020; Otieno et al.,2024; Funk et al., 2023). Although some studies have looked into ways that practitioners have tried to do this (e.g. see Walker, 2021 and Hermans et al,. 2022 for examples) some questions remain. For instance, how might warning messages be communicated in ways that do not undermine/patronize indigenous belief systems? How can discrepancies which sometimes arise between scientifically derived information and farmers perceptions of climate realities be reconciled? (Solano-Hernandez et al., 2020).

Risk communication models that account for the behavioral nuances of adoption, such as consumer choice models with relaxed rationality assumptions or mental models that align messaging with farmer perspectives, could provide a stronger theoretical basis for adaptive decision-making.

Continuous EWS interventions face sustainability challenges, especially in changing policy landscapes. Research could address the effects of evolving political environments on EWS credibility, community buy-in, and funding stability. Institutionalizing EWSs, with stable support and adaptability to shifting needs, could enhance their long-term effectiveness.

Ultimately, addressing informational, attitudinal, and behavioral barriers through well-designed risk communication will be essential for supporting climate change adaptation. Future research that hones methods for effective risk messaging and clarifies potential trade-offs in EWS updates will enable decision-makers to allocate resources effectively and enhance farmers’ resilience in the face of growing climate challenges.

Blog written by Nnenna Ogbonnaya-Orji.