Introduction

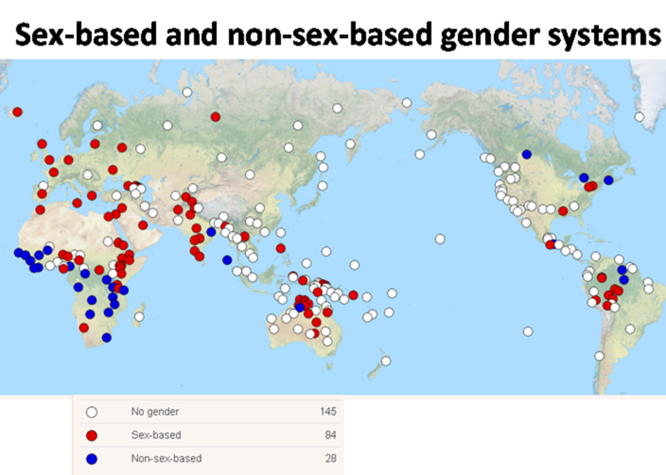

Language is an important cultural institution in human society. The World Bank (2019) estimates that 38 percent of world languages have grammatical gender, which can be defined as a system of word classification in which words are grouped into categories or “genders”. In the last decade, gendered language has attracted increasing attention from social scientists as a force shaping socio-economic inequalities and development outcomes. Evidence from recent research in economics, psychology and management has shown that the gender system of a language has causal impacts on wage inequality, female labor force participation, gender gap in math achievement, innovation output, gender norm attitudes, among others.

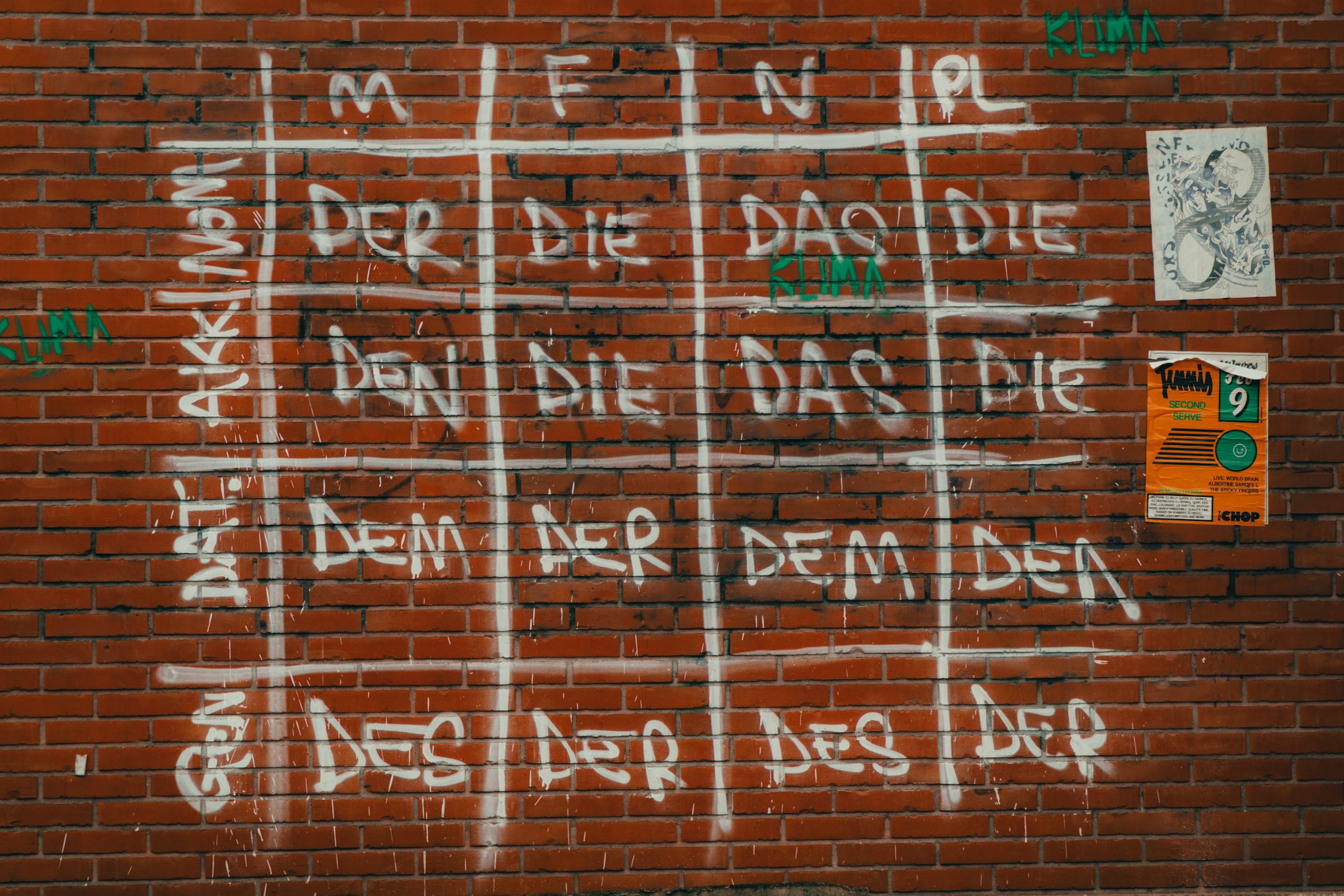

Grammatical gender in language may or may not be linked to biological sex. In some languages, gender is based on an animacy (living/non-living) rather than a male/female distinction, such as in Swahili. Grammatically gendered languages vary in the specific location in syntax to which gender is attached (Kramer 2016). Some languages gender-mark nouns only, whereas in others gender is marked in various locations in the syntax. Gender can manifest in (1) adverb modifiers: for example, “la voiture” the car, “le marteau” the hammer in French; (2) adjective modifiers: for example, “la nouvelle voiture” the new car, “lemarteau perdu” the lost hammer in French; (3) pronouns: For example, the sex-based pronominal gender system she/he/it in English; and/or (4) verbs: For example, “молодая медсестра пошла в больницу” – “The young nurse went to the hospital” in Russian. Here, the modifier and the verb are both conjugated to the female gender in agreement with the gender of the subject. Arabic is another language where verbs are gendered in accordance with the gender of the subject. Some languages whose noun gender system is sex-based do not indicate sex in pronouns, such as Tamil and Farsi; whereas some gender-mark pronouns only, not nouns, such as English.

Operationalizing grammatical gender as an independent variable

What does genderedness of a language capture?

Explanations vary regarding the mechanism through which grammatical gender impacts decision-making and behavior. Proponents of one view posit that grammatical gender, like other language structures, arises from evolutionary pressures shaping patterns of reproduction and the division of labor in the history of a given society (Dahl 2004; Johansson 2005; Galor et al. 2018; Shoham 2019). Language structure, along this view, has been described as “institutional memory” (Hicks et al. 2015), “gender roles mirror” (Shoham 2019) and “a vehicle for cultural transmission” (Gay et al. 2013). Therefore, grammatical gender encodes historical institutions and acts as a proxy for their effects. Another view suggests that variations in language structures give rise to differences in individuals’ reasoning, learning, and other mental activities (Whorf 1956; Lucy 1997).

Exploring mechanisms is especially relevant to policy because determining what policy can change and cannot change requires elucidating the source of constraints or shifters of preference. It is difficult for policy to cause wholesale change in social and cultural norms. So if gendered language has no independent effect apart from mediating that of social and cultural norms, language reform policy has little leverage. However, if gendered language alone constitutes a source of psychological constraints or primers with impact on behavior or decision-making, language reform policy can be an easy-to-implement and low-cost way of attaining desired change in agents’ behavior or decision-making.

Language as a measure of culture

Language structures are part of culture, broadly understood. However, unlike other cultural features which evolve independently, language structures are highly correlated with other subsets of culture. Attributing autonomous causal power to gendered language faces difficulty given the presence of a rich set of confounders (Maviskayan 2015). For example, what historically caused the emergence of certain features of linguistic structures may directly shape the outcome variable, eg. historical migration and labor specialization patterns.

Scholars have used language structure as an instrumental variable for culture. For example, Licht et al. (2007) use the grammar of pronouns as an instrumental variable to study how countries that favor autonomy, egalitarianism, and mastery exhibit less corruption. However, this approach assumes that language structure has no autonomous, unmediated causal impact on individual propensity to corruption, which is contradicted by the linguistic relativity hypothesis. Studies, such as Gay et al. (2013), have shown that linguistic structures can have significant effects on socioeconomic outcomes after controlling for measures of culture.

Measurements

What constitutes a grammatically gendered and a grammatically genderless language is subject to contested definitions. Authors of the World Atlas of Language Structures (WALS) articulate four gender-related grammatical features of language, each of which can be represented in a dummy variable as follows (summarized in Gay et al. 2013):

| Measurement strategy | Definition | Binary/continuous | Adoption (# articles) |

| Gay I (2013) | GII = SBI + NGI + GAI + GPI | Continuous (0-4) | 6 |

| Gay II (2018) | GII = SBI × (GPI + GAI + NGI) | Continuous (0-3) | 1 |

| Jakiela & Ozier (2018) | GG = SBI × GAI | Binary | 2 |

| Stahlberg (2007) | A grammatically gendered language is one where every noun is assigned feminine or masculine or neuter gender. It is distinguished from natural gender languages and genderless languages | Binary | 1 |

| Givati & Troiano (2012) | The number of cases of gender-differentiated pronouns | Continuous | 1 |

| Mavisakalyan (2015) | A language is either highly gendered, mildly gendered, or gender neutral | Continuous (0-2) | 1 |

Other measurement strategies exist: in Jakiela & Ozier (2018) define grammatical gender by requiring formal gender assignment (GAI=1), combined with sex-based assignment (SBI=1) to create their metric (GAI × SBI); Stahlberg et al. (2007) classify languages into three categories: grammatical gender languages (nouns have gender), natural gender languages (no grammatical gender, but pronouns may reflect sex), and genderless languages (no gender in nouns or pronouns). Givati & Troiano (2012) quantify grammatical gender as the number of gender-differentiated pronouns, e.g. Spanish has four cases of gender-differentiated pronouns (third-person singular, first-person plural, second-person plural, and third-person plural). Lastly, Mavisakalyan (2015), building on Siewierska (2008)’s categorization of languages based on the intensity of gender distinctions in pronouns into six types, offers a revised framework with three types: highly gendered (Gender distinction in third-person and also the first- and/or the second-person singular pronouns), mildly gendered (Gender distinction in third-person singular pronouns only), and gender-neutral (No gender distinction in pronouns).

Table 2. Grammatical gender features in WALS

| 0 | 1 | |

| Sex-Based Intensity (SBI)[1] | languages without a sex-based gender system | languages with a sex-based gender system |

| Number Gender Intensity (NGI) | languages with three or more genders or with no gender distinctions | languages with exactly two genders |

| Gender Assignment Intensity (GAI) | languages with no gender assignment system or where the gender assignment system is only semantic[2] | Languages where the gender assignment system is both semantic and formal[3] |

| Gender Pronouns Intensity (GPI) | languages which do not distinguish gender in pronouns (or does so only in the third-person pronoun). | languages with a gender distinction in third-person pronouns and also in the first and/or the second person |

Existing Evidence

A large body of work in psychology exploring the effect of gendered language on psychological processes and attitudinal and cognitive outcomes exist; however, the recent economics literature has increasingly focused on socioeconomic outcomes. Existing literature on the effect of gendered language predominantly find a negative effect of gendered language on gender equality, understood as women’s attainment, or the parity between men and women, of socioeconomic outcomes. These outcomes include the Global Gender Gap Index score (Prewitt-Freilino et al. 2012); education attainment (Davis & Reynolds 2018; Galor et al. 2020); labor force participation (Givati and Troiano 2012; Gay et al. 2013; Mavisakalyan 2015; Jakiela and Ozier 2018; Gay et al. 2018); political participation (Gay et al. 2013), access to land and credit (Gay et al. 2013); representation of women on corporate boards (Santacreu-Vasut et al. 2014; Pisera 2023); gender wage gap (Van der Velde et al. 2015; Shoham & Lee 2018); entrepreneurship activity (Hechavarría et al. 2018; Xie et al. 2021); women’s math performance (Kricheli-Katz & Regev 2021; Cohen et al. 2023).

Exceptions include Del Caprio & Fujiwara (2023), focusing on women’s application to online tech jobs, which finds no evidence of a significant effect of changing the gendered form of address in job ads except for fields where there is existing substantial representation of women; and Santacreu-Vasut et al. (2013), who find a positive relationship between gendered language and gender equality, although equity is legislated (gender quota in a parliament) hence possibly reflecting that a society with gendered language is more likely to require a quota for representation than a society able to move toward equality more naturally.

[1] SBI includes nomial as well as pronominal sex-based gender system. English, for example, is considered to have SBII=1 since it has sex-specific pronouns, although it is otherwise usually considered a grammatically genderless language.

[2] Semantic gender assignment is based on the inherent meaning or characteristics associated with nouns. Nouns are assigned to gender classes based on their semantic properties, such as biological sex, animacy, or natural gender. In this system, the gender assignment of a noun is often predictable based on the noun’s meaning, eg. “la grand-mère”, the grandmother; “le fils”, the son.

[3] Formal gender assignment, also known as grammatical or arbitrary gender assignment, is based on the form or shape of nouns rather than their inherent meaning. Nouns are assigned to gender classes based on grammatical rules and patterns within the language, which may not correspond to natural or semantic gender distinctions, eg. “la voiture”, the car; “le Pakistan”, Pakistan.

| Grammatical gender | A system in which nouns are always categorized into classes, which are often but not always linked to biological sex |

| Syntax | The order in which words are arranged in a sentence |

| Syntax agreement | Agreement occurs when a word changes form depending on the other words in a sentence to which it relates. |

| Semantic | Relating to meaning in language |

| Modifier | An adjective or an adverb used to modify a noun |

| Lexical | Relating to the words or vocabulary of a language |

| Lexical gender | Semantic property carried in lexical units, such as “mother” and “son” in English which assign female or male quality to the referent |

| Referential gender | A sub-category of lexical gender where referential lexical units, ie. pronouns have gendered semantic property, such as “he” and “she” in English |

| Social gender (also called natural gender) | Socially imposed dichotomy of masculine and feminine traits associated with nouns, such as “trucks” (masculine) v. “lamp” (feminine), which often but do not always coincide with grammatical gender |

| Generic masculine (also called false generics) | Male generic usage in cases of gender-indefinite reference. E.g., the singular generic masculine in English, “An American drinks his coffee black”; the plural generic masculine in Spanish, “Los olímpicos han vuelto” (The Olympians have returned). |

| Speaker-gender dependent expressions | Expressions or linguistic structures which male or female speakers of the language ought to use exclusive to their gender, eg. politeness expressions reserved for women in Japanese; separate languages for men and women in the Ubang community in Nigeria |