Mobile money, or the use of mobile devices to send, receive, and transfer money digitally, is becoming more popular around the world and offers a potential pathway to increase financial inclusion among low-income populations in developing countries. According to the World Bank, financial inclusion means having access to useful and affordable financial products and services that are delivered in a responsible and sustainable way. Financial inclusion develops the opportunity for people to save, spend, and receive money more sustainably and efficiently than if they were excluded from financial systems.

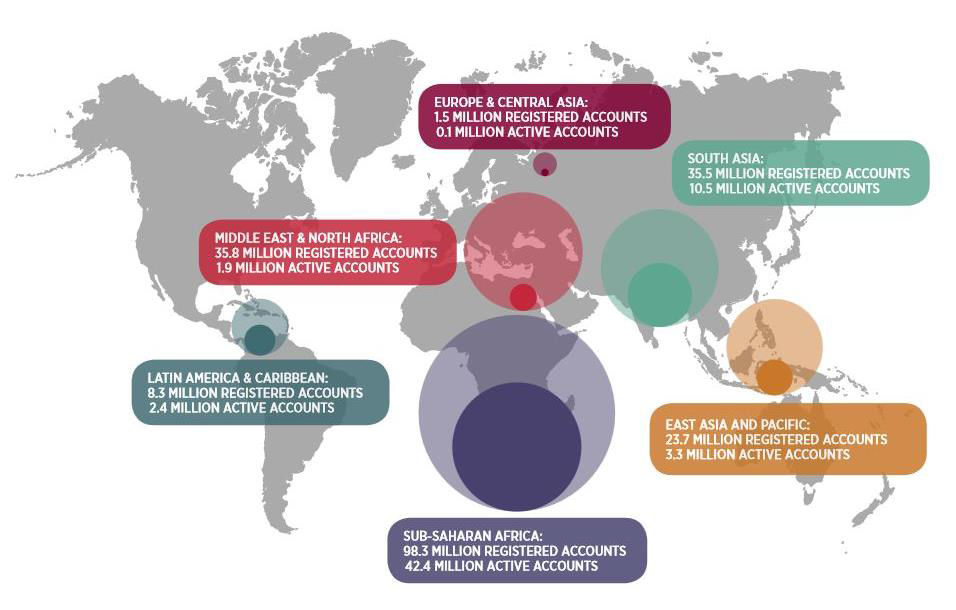

Inclusion through the use of mobile money is especially important for low-income populations who do not have access to traditional financial services like banks. According to the 2014 Global Findex Database, 12% of adults in Sub-Saharan Africa have a mobile money account, representing over a quarter of those in Sub-Saharan Africa with some sort of financial account. Account-holding rates are relatively higher among low-income populations, indicating some potential for mobile money to reach those historically unable to access traditional services due to income, geographic, or mobility barriers. Financial inclusion and mobile money usage is expected to increase as the more than 270 mobile money services in 93 countries expand and telecom coverage spreads.

Source: Pémocaud & Katakam, 2013, p. 22

Protecting the Consumer

The spread of mobile money has been accompanied by an increase in questions about consumer protections and system regulations. As mobile money markets expand, protecting consumers from risk and ensuring that they have the information required to make informed decisions may increase confidence and trust in mobile money systems, leading to even higher usage rates.

When consumers perceive or encounter problems within mobile money systems that expose them to risk, it can be expected to decrease their trust, uptake, and use of the services. MicroSave, a financial inclusion consulting firm, performed a review on consumer concerns in Bangladesh, Philippines, and Uganda that found that mobile money customers are primarily concerned with service downtime, agent illiquidity (inability to access funds), fear of sending money to the wrong number, and the charging of unauthorized fees by agents. Other concerns reported include user interfaces that are complex and confusing, poor customer pathways for addressing issues, nontransparent fees and terms, fraud, and inadequate data privacy and protection. These issues of ease of use and transparency are heightened for those with low or no literacy, especially considering the appeal of mobile money in low-income countries. Attending to these concerns has the potential to further increase mobile money usage and financial inclusion.

While mobile money providers could reasonably aim to implement appropriate systems to address these issues, solutions that adequately protect consumers and efficiently allocate risk are unlikely without government involvement. Government-imposed consumer protections and industry regulations can provide incentives and support structures to address customer concerns. These regulations may come with tradeoffs between the speed, spread and equity of providing mobile money, affecting cost, usage rates, innovation potential, and the number of providers. Therefore, when developing regulations, governments must balance the importance of promoting access and innovation with providing acceptable levels of consumer protection.

Regulating the Industry

EPAR examined the regulatory environment for digital financial services (DFS), such as mobile money, in 22 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, and South America. For each country, we analyzed the regulatory environment, reviewing documents to learn how key issues in mobile money consumer protection, such as transparency, dispute resolution, prices and fees, and fraud and other sources of consumer losses, were addressed.

Of the 22 countries reviewed, 18 have three or more active mobile money services provided through private telecom companies or banks. Five countries have mobile money systems led by banks while 16 allow non-bank entities (mostly telecom providers) to be mobile money operators. In Ecuador, the Central Bank is the only mobile money provider allowed in the country.

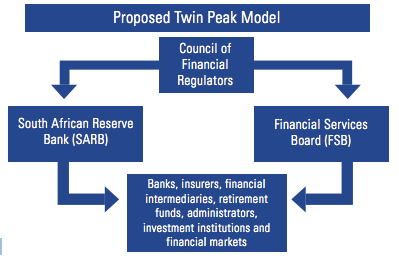

Every country studied has a financial regulator in charge of DFS regulation to ensure market standards and consumer protections. This regulator is often the central bank, but some countries have developed independent regulatory agencies. An alternative form of financial regulation is the Twin Peaks model that is used by Indonesia, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru and is being implemented in South Africa. This model creates a separate regulator in the hope that increased transparency and consumer protections will be a priority. The proposed model in South Africa is depicted below.

Source: KPMG, 2013, p. 5

Pricing the Competition

One area of consumer concern is prices and fees for mobile money services. Mobile money’s appeal in expanding financial inclusion to financially-marginalized communities means that pricing structures must be competitive for low-income users. Government-imposed limits on transaction fees help to limit user costs, as does competition among providers. Regulators covered in our review have acknowledged this concern with regulations that cover anti-competitive pricing, third party imposed fees, price monitoring, and dormant account management. However, mobile money also offers a tax revenue source for governments, especially in countries where low-income populations operate in the informal economy. Our review shows that governments have taken a variety of tax-related actions, ranging from imposing them on the provider or consumer to (on the opposite end of the spectrum), eliminating them to spur growth and competition. The full EPAR report includes more detail about specific regulations by country and findings on approaches to regulating different areas of consumer protection.

As mobile money usage grows, attention to the realized outcomes from each country’s choices around consumer protection can inform emerging and future healthy regulation frameworks.

By Jack Knauer

Summarizing research by Leigh Anderson, Travis Reynolds, Caitlin Aylward, Pierre Biscaye, Brian Hutchinson, and Rowena Sace